If you’ve spent more than five minutes thinking about keto, you’ve tried to figure out what carbs versus net carbs actually means.

Avoiding all carbohydrates is impossible. Vegetables contain carbs. Nuts contain carbs. Even foods marketed as “keto” contain carbs. The real question is not whether carbs exist in your diet, but which carbs actually count for the goal of staying in ketosis.

That’s where “net carbs” comes in. And that’s also where things quietly go wrong.

What “Net Carbs” Actually Means (and Why It Exists)

Net carbs is not a term defined by the FDA. You won’t find it regulated on nutrition labels. It exists because people following low-carb or ketogenic diets needed a practical way to estimate carbohydrate impact, not just total quantity.

In simple terms:

Net carbs are carbohydrates that meaningfully affect blood glucose and, by extension, ketosis.

Some carbohydrates pass through the body largely undigested. Others are absorbed and metabolised quickly. Treating them as identical makes dietary bookkeeping inaccurate—especially on keto, where margins are narrow.

Net carbs emerged as a working concept, not a legal one.

That distinction matters.

Why Food Labels Make Net Carbs So Confusing

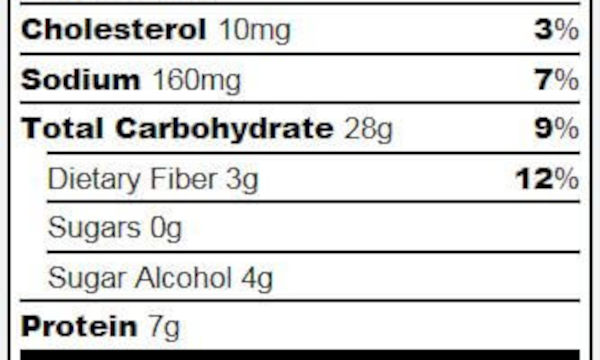

In the United States, the FDA requires manufacturers to list total carbohydrates on nutrition labels. This includes:

- Sugars

- Starches

- Fiber

- Sugar alcohols

Manufacturers are then allowed to highlight or calculate “net carbs” themselves, usually by subtracting fiber and sometimes sugar alcohols.

The problem is not the math.

The problem is what gets subtracted.

Because “net carbs” is not a regulated standard, two products can both claim “2g net carbs” while behaving very differently in the body. This is why keto bars, cookies, and snacks so often derail people who are otherwise careful.

In short:

“Net carbs” on packaging is a marketing term, not a guarantee.

Why “Only Total Carbs Matter” Is Also Incomplete

At the other extreme, organisations like the FDA and the American Diabetes Association emphasise total carbohydrates as the most reliable number for the general population. From a public-health and labeling perspective, this makes sense.

Total carbs are:

- Clearly defined

- Standardised

- Harder to manipulate

But ketosis is not a general dietary goal. It is unusually sensitive to carbohydrate intake. Treating fiber and rapidly absorbed sugars as metabolically identical is accurate for labeling and imprecise for keto.

Both perspectives are internally consistent. They just answer different questions.

The mistake is treating either one as universally sufficient.

The Practical Middle Ground for Keto

For ketosis, you don’t need to reject total carbs entirely—or blindly trust “net carbs” on the front of a package.

What you need is a conservative, repeatable rule.

Here it is:

Start with total carbohydrates.

Subtract only carbohydrates that are reliably non-impactful.

Ignore manufacturer net-carb claims.

This approach works because it:

- Anchors on FDA-defined numbers

- Avoids marketing distortions

- Still reflects how keto actually functions in practice

Safe Net Carb Deductions (Commonly Accepted on Keto)

The following carbohydrate categories are widely treated as non-impactful for ketosis when consumed in typical amounts:

Dietary Fiber

- Naturally occurring fiber is not digested into glucose

- Commonly subtracted from total carbs

- Listed clearly on nutrition labels

Erythritol

- A sugar alcohol largely excreted unchanged

- Minimal glycaemic impact compared to other sugar alcohols

- Often treated as safe to deduct by keto practitioners

These deductions are not about perfection—they’re about predictability.

Carbs You Should Not Deduct (Despite the Label)

Many products subtract carbohydrates that behave very differently from fiber or erythritol. This is where most keto frustration originates.

Be cautious with products containing:

- Maltitol

- Sorbitol

- Isomaltooligosaccharides (IMOs)

- “Modified” or “resistant” fibers used primarily in processed bars

These ingredients are frequently marketed as low-impact but are at least partially absorbed and can meaningfully affect carb totals for ketosis.

If a product’s low net-carb claim relies heavily on these, the claim deserves skepticism.

The Simple Rule That Actually Works

You don’t need lab tests, ketone meters, or ingredient paranoia.

Use this:

A Practical Keto Net Carb Rule

- Start with FDA total carbohydrates

- Subtract dietary fiber

- Subtract erythritol only (if present)

- Treat everything else as a real carb

- Aim to stay under ~30–50g per day, depending on your tolerance

If a bar claims “2g net carbs” but fails this test, trust the math—not the marketing.

Why This Matters More Than It Seems

Most people don’t “fail” keto because they lack discipline. They fail because food labels quietly shift the definition of a carb underneath them.

By anchoring on total carbs, deducting conservatively, and ignoring unregulated net-carb claims, you avoid both extremes:

- The impossibility of zero carbs

- The false comfort of engineered keto snacks

That middle ground is not complicated. It’s just rarely explained clearly.

And once you understand it, keto becomes far less mysterious—and far more predictable.

References:

https://diabetes.org/food-nutrition/understanding-carbs/get-to-know-carbshttps://www.webmd.com/women/features/net-carb-debate